Incident commanders and firefighters are consistently presented with new unique challenges and heightened risks on the job. Yet, many fire and rescue services are still using incident command strategies that haven’t adapted to meet 21st century needs. Below, we’ll delve into why public safety agencies should consider moving beyond their current incident command system (ICS) board to combat these new challenges and risks.

Modern Fire Incident Command

Incident command strategies have changed considerably over the years. In the United States, there are national standards in place for coordinating information and people, born out of the FIRESCOPE project of the 1970s.

All incident commanders have multiple considerations to keep in mind on the incident ground. We see modern fire ground commanders contemplating structural elements, tenability, rescue and life safety considerations, proper apparatus placement, weather, staffing, water supply, and in some instances multiple incidents going on at the same time to factor into their decision making.

With all of these different and unique factors in play, fire services need to adopt an incident command strategy that can successfully address these new concerns and lead to more effective incident management.

The Incident Command Systems Board

We see fire services around the world using a combination of a pen and paper or the erasable whiteboard to assign resources to positions, create tactical plans, mark hazards, and designate points of interest.

Often, we see commanders mapping out their strategy on a whiteboard and then orally communicating instructions to staff via radio or verbally during a short huddle around the command car.

This is where the problem lies. The incident command whiteboard is not equipped and designed to meet the needs of today’s increasingly complex situations. When a large-scale incident occurs, commanders using whiteboards are at a distinctive disadvantage compared to their colleagues using incident command software or other incident management technology. Below I look at key areas in which the ICS board is limiting commanders’ capabilities to effectively manage modern emergencies.

Static Information

Imagine the following scenario. A crew responds to what dispatch believes to be a standard working residential structure fire. Upon arriving on scene, incident commanders do a size-up and create a tactical strategy based on the knowledge from dispatch and what their senses told them both responding and arriving on scene.

As the incident progresses things begin to change very quickly. Hazardous materials are identified in a storage space, children are discovered hiding in an upstairs bedroom during the primary search, a wall caves in unexpectedly during operations, and multiple news media sources arrive looking for someone to speak with.

Everything that happens at an incident impacts a commander’s next moves. The problem is that the current ICS board cannot automatically update as new information comes in.

Does the physical ICS board automatically update from CAD to show requested and new available resources? Can the board let you know the anticipated arrival times of those resources? Does the board display crew information, length of time on scene, or time spent on an assignment?

As the scene grows and additional units are asked to respond, do commanders have the space on the board to manage those new resources?

When commanders receive reminders from dispatch or aides, complete items off local benchmarks, perform analytical risk assessments, or review wind and weather conditions, they are forced to manually document that information somewhere.

Furthermore, the ICS board makes it difficult to track those changes and plan for new forward strategies. Even if commanders have an erasable whiteboard where they can make edits, that inevitably means writing over previous resource assignments or annotations, which equals the loss of crucial and historical information.

Once the incident is complete and one begins to create the incident report, it can be very difficult to keep track of what happened when and who did what and why. Were all benchmarks logged? Does incident information located in different spots need to be gathered to complete the report such as dispatch files, recorded radio traffic, and the white board and paper drawings?

The whiteboard truly displays only a limited picture of what actually occurred on scene, and may not even show which strategies the commander implemented. Sections might be crossed out, erased, or otherwise unreadable.

This leads to a few key problems.

- After-incident reporting may be inaccurate, which makes it difficult or impossible to correctly evaluate how tactics worked and plan for future incidents and scenarios.

- Should legal issues arise, commanders may be unable to validate their command strategy since they lack clear historical information on the chain of events and why they chose to make certain decisions.

Lack of Shared Visibility

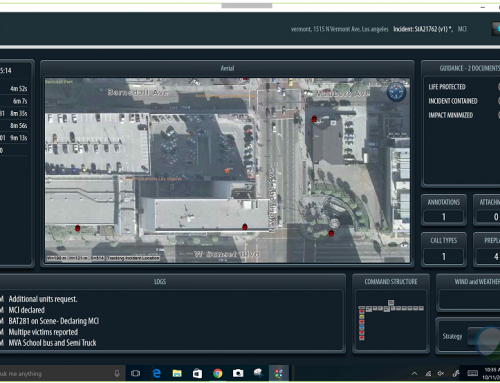

For complex and growing incidents, the sharing of critical information in real-time can be extremely useful to allow for a common operating picture and improve collaboration among multiple jurisdictions or agencies.

When using a notepad or whiteboard, it can be difficult to communicate mission-critical information efficiently. Only people directly in sight of the board can view what’s being identified and drawn out.

Firefighters on the fire ground, officers from other fire and rescue services, and commanders at the emergency operations center (EOC) have no visibility into the actions the incident commander is taking on-scene.

Commanders can relay some of their tactics verbally over the communications system which can clog up valuable radio space. Theoretically, commanders could also take photographs of their ICS board and send that information to the EOC or other command staff on scene, but that is not a common practice.

The inability to share the correct instructions quickly can be especially costly during a large-scale incident where every second and detail matters.

Sharing detailed information quickly, easily, and effectively is one area in which the ICS board falls short when compared to other incident command technologies available today.

One benefit of the new incident management technologies is that the same annotated maps, floorplans, incident action plans (IAPs), or photographs that the commander is using can be shared instantly among all connected users to the command system software, either on-scene or at the EOC. Particularly if there are multiple units at a scene, this capability can have a big impact on incident mitigation and help commanders manage the scene and personnel effectively to prevent loss-of-life.

Administrative Backlog

Lastly, traditional ICS boards create an unnecessary administrative burden. Since the whiteboard is a non-electronic document, any handwritten documentation and scene information must be separately transferred to an ICS form, IAP, checklist, etc.

When command data is not automatically recorded, it can lead to hours of unnecessary time spent filling, researching, and copying in the correct information.

Many forms of incident management technology automatically log and transfer incident data to an agency’s records management system (RMS). Thus, all gathered and saved incident information can be located digitally in one place and attached to the correct incident in the RMS.

Although many fire incident command tactics and strategies have held up over time, there are significant improvements that can be made when it comes to the current ICS board. While some departments prefer the ICS board because of its familiarity, there are multiple key areas in which a whiteboard/notepad falls short in comparison to new and available technologies.

Fire and rescue services across the world are choosing to implement incident command software and other incident management technologies to effectively promote and assist in Life Safety, Incident Stabilization, and Property Conservation.

With new risks in the fire service continually presenting themselves, it’s important to continually evaluate command options that will best serve departments both now and in the future.

It’s time for departments to consider moving past the ICS white board and implement a 21st century fire incident command method.

Today’s blog was authored by our own Brad Reineke, a retired career Engineer/Medic from West Des Moines, Iowa.

If you enjoyed this post, check out some of our related articles:

Why Incident Management Technology is Crucial for Command

How First Responder Technology Reduces Injuries and Line-of-Duty-Deaths

To learn more about Adashi’s incident command software, visit our C&C product page.

Bradley Reineke is the Adashi National Sales Director. He is a retired career firefighter and has numerous years of experience in public safety.

![[Infographic] 8 Ways Adashi’s Technology Improves Incident Command](https://www.adashi.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/8-WAYS-ADASHIS-TECHNOLOGY-IMPROVES-INCIDENT-COMMAND-1-500x383.png)

![[Infographic] The History of Fire Incident Command in the US](https://www.adashi.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/The-History-of-Fire-Incident-Command-in-the-US-1-500x383.jpg)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.